A co-authored blog by Frances Forshlager and Dr Gai Lindsay

Remember when it felt like the whole world was quiet? When there was not even one sound or vapor trail in the endless dome of blue sky above? When cars largely stayed in garages and birdsong reminded us of things we had missed hearing in our everyday rush?

During the pandemic lockdowns – while online platforms (and ramped up pressure in education contexts!) kept us all busy and somewhat anxious in a cycle of groundhog day effort and wonderings – my daily neighbourhood walks offered moments of pause, deep breaths, offline headspace….and a daily recalibration.

Connections with nature continue to offer important invitations to pause…and to connect, for both children and educators.

When visual arts materials connect with inspirations in the natural world, they invite us to see, to engage and to visually communicate – in responsive moments of joyful wondering and nature connection.

I’m delighted to welcome Frances Forshlager as a guest writer on the blog.

Frances is a passionate educator whose work beautifully weaves together nature, creativity, community and Learning on Country. Her reflections invite us to slow down, look closely and recognise the profound ways children form relationships with the natural world.

In this piece, Frances explores how authentic materials, sensory encounters and artistic expression support children to connect emotionally and creatively with the landscapes around them. It’s a gentle reminder of the power of place, presence and noticing.

Following Frances’ article, I will wrap up with some reflections of my own.

My name is Frances Forshlager and I’m based in the Southern Highlands NSW. Presently I work part time at a local preschool whilst sharing my creativity and experiences through my website and social media pages under the title ‘The Nature of Creativity’.

Follow Frances on LinkedIn or Facebook

I would like to acknowledge the Gundungurra and Dharawal people past, present and emerging who are the Traditional Custodians of Bundanoon where I walk, work and live.

“The ancient spirit are all around us. They awaken from their slumber when someone is willing to listen. They have many messages. To hear them, the student must be quiet in mind, body and spirit, for profound truth does not need to be yelled. In this sacred space of quiet whispers, reflection can take place, and the earth breathes more easily.” – Paul Callaghan ‘THE DREAMING PATH’.

Threads of competency and investigation

Part of our identity as educators is the role of researcher, facilitator and advocate of pedagogical innovation to co-learn and collaborate with children. Each role allows threads of competencies and investigations to be woven into a program of rich context and endless possibilities through slow pedagogy.

Connection to place is at the core of my teachings along with sharing these joyous findings with educators beyond the classroom walls.

Place can be located within the diversity of your local community, encounters on Country or returning to same place to reflect seasonal changes.

It really depends on where you find a sense of belonging and feel spiritually in tune with the spaces and places in your environment.

To produce a rich tapestry of learning with children, it is important to open your own perspective to embrace possibilities with awe and wonder, to really notice colours, textures, foliage and fauna.

DEFINING COUNTRY

In Frances’ blog post, she capitalises the word Country. For the benefit of international readers and those not familiar with the Aboriginal Australian use of the word sense, Country is a holistic concept that includes land, sky, waters, ancestors, stories, languages and all living beings. It describes a reciprocal relationship in which people care for Country, and Country in turn cares for them; shaping identity, belonging and responsibility.

Children’s perceptions of Country are filled with innocence and fresh appreciations which are pure and raw.

Each child has the gift to weave these threads together through daily encounters in nature whilst many educators have forgotten that the smallest discoveries or gestures often produce the biggest outcomes.

Children form bonds on Country very quickly, and when you listen to how they address these living things, they often use pronouns.

They’ll use he or she for their own favourite flower, plant or family of trees. Children have learnt to create their own stories with native characters.

Each place brings opportunities to explore your own creative skills, rethink the aesthetics found in nature, in life cycles, and in the elements and importance of time. You start to understand changes within the landscape and challenge yourself to use this newfound knowledge and materials in learning spaces

Through regular encounters on Country, you can start to form organic bonds within the environment and understand the rituals of the landscape and its occupants. Favourite walking tracks brings gentle reminders to travel the pathways of those before you. Bring awareness to all your senses as you stop, pause and listen. The traces may only be visible once your feet are grounded.

Feel the earth beneath your feet, breathe in the smells of diversity, admire the abundance of life. Witness the interconnected relationship between culture and nature which has been deeply interwoven for centuries. To share knowledge, you need to obtain knowledge, be the citizen who researches traditional names of place, flora, fauna and people.

Taking time to pause in nature proves opportunities to explore the landscape through the lens of an artist. Learn to take time to ‘close in’ on the subject or object from various angles. Looking for the finer details such as contours, formations, patterns, textures and colours.

Take photos of a single weed to uncover its beauty or squiggly marks on gumtree bark which are excellent examples of mark making for drawing experiences.

Record the wind channelling through trees to inspire children to recreate the flow with easel painting.

Finding the extraordinary in the ordinary provides endless possibilities.

It must be noted that educators and children need understand the importance of returning materials back to Country which we have borrowed for artistic experiences. For nature to continue the cycle of life materials need to break down organically.

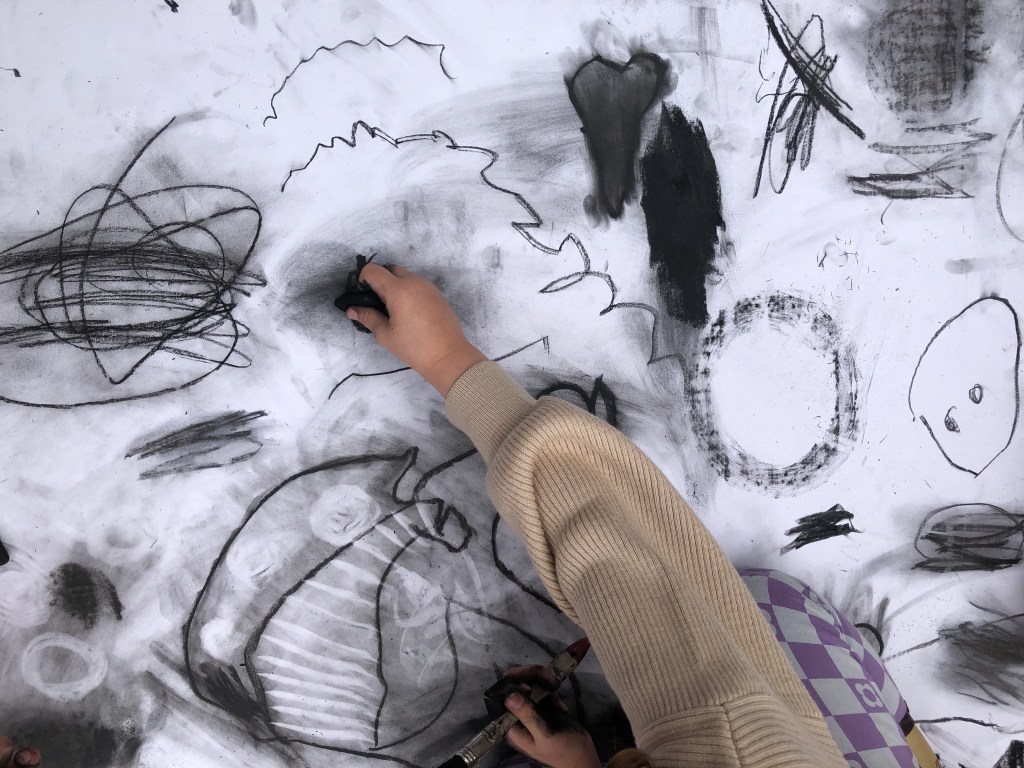

When focused on one medium, every child will produce different interpretation of the same subject.

This provides the educator an insight into the child’s technique, skills and style.

Charcoal is a material which can be sourced on Country as fire plays and important role in Indigenous culture. Each piece of charcoal represents the end of a life cycle of a living thing.

I’m of the opinion that when we work with charcoal it comes alive again through visual expression.

Art Example One

The concept of tree spirits can be explored by using earthenware clay and natural loose pieces gathered on Country. Spirits are the source of all life and connection, linking past, present, and future, and open to explanation for children if researched accurately.

A clay ball is formed, then pressed against a tree trunk to form an oval. Traces of the bark imprints represents the lines of ageing skin. The clay is removed and decorated with natural loose parts to represent facial features. Once complete the sculpture is placed against the trunk again. Through the passage of time, the work will break down and return to the earth, where the spirit created by the child is released.

Art Example Two

One of the significant discoveries children and I have found on Country are bleeding trees. These native eucalyptus trees produce a material not commonly associated with visual expression but when viewed in a natural sunlight the sap sparkles like rubies.

Children associate the sap with blood and regard exposed areas on trees are open wounds. An encounter where children display empathy to another living thing because of their bond. Children have used pieces of fabric to cover the wound – to heal the tree.

Pieces of sap are gathered and used to create three-dimensional sculptures such as bird’s nest.

The sap can be used for clay work or collage experiences using natural materials.

When exposed to heat a liquid is produced which is used in bundle dyeing to obtain reddish tones.

The most important part of being on Country or visiting your favourite place are the people you cross paths with. Their art, culture, knowledge and values become lessons for storylines and learning spaces. When the past is communicated by those who lived it, we must be willing to listen and respect.

With permission these conversations should be shared with children to not only learn about the past but for emerging relationships for their future. Invite these visitors into your learning spaces as an opportunity to revisit artistic skills through a broad range of conversations and materials. We need to open our hearts and minds to enable new possibilities for the young whilst standing side by side with the old.

A final reflection from Dr Gai Lindsay

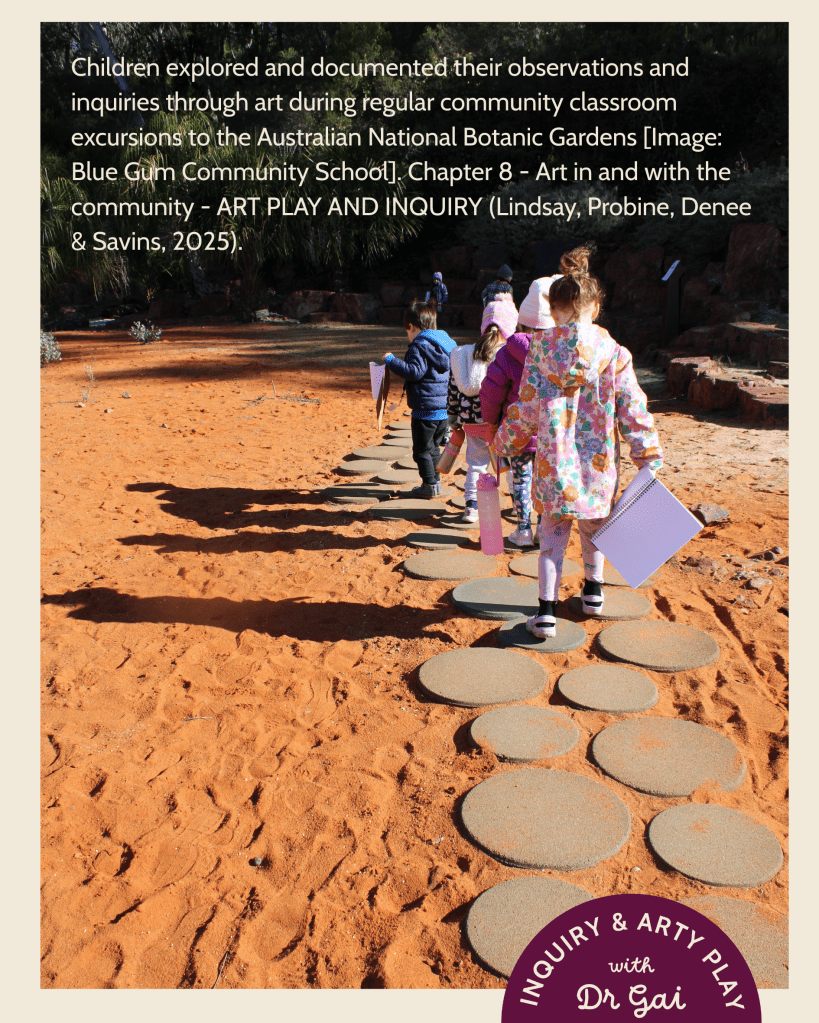

Stepping beyond the gate—and beyond familiar assumptions about children’s art—opens rich possibilities for more meaningful, connected and imaginative making (Lindsay, Probine, Denee & Savins, 2025).

In a fast-paced, technology‑saturated world, children still have the right to “visual, open‑ended and playful opportunities to explore ideas, make their thinking visible and communicate what they know, understand, wonder about, question, feel and imagine” (Lindsay, 2023, p.7). When children’s art making is inspired by real observations, encounters and relationships with people, places and materials, it becomes a powerful language for expression, connection and community.

Pelo (2013) reminds us that time spent walking, noticing, naming and dwelling with the land nurtures curiosity, belonging and new stories. Indeed, developing an ecological identity grows from recognising our interdependence with the natural world (Thomashow, 1996). This truth has long been understood with Dewey (1900) emphasising the educational value of firsthand experiences with real materials and processes, while Vecchi (2010) more recently highlights children’s natural empathy with their surroundings as a bridge to relationships with others.

So what might this look like in practice?

If your visual arts program feels stuck in repetition or routine, perhaps the next step is simply to look outward.

By bringing the textures, colours and provocations of the natural world into children’s aesthetic encounters and visual arts experiences, we invite wonder, offer new possibilities for expression and expand the stories they can tell; both within and beyond the early learning setting.

References

Dewey, J. (1900). The School and Society. The University of Chicago Press.

Lindsay, G. (2024). Visual arts learning: Beyond the easel and beyond the gate. Play

Outdoors Magazine. 4(4), p. 28-30. https://playoutdoorsmagazine.ca/

Lindsay, G.,Probine, S., Denee, R., & Savins, D.(2025). Art Play and Inquiry: The Why, What and How or visual arts with young children. Routledge.

Thomashow, M. (1996). Ecological identity: Becoming a reflective environmentalist. The MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262700634/ecological-identity/

Vecchi, V. (2010). Art and Creativity in Reggio Emilia: Exploring the role and potential of ateliers in early childhood education. London: Routledge.